Aaron Copland on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

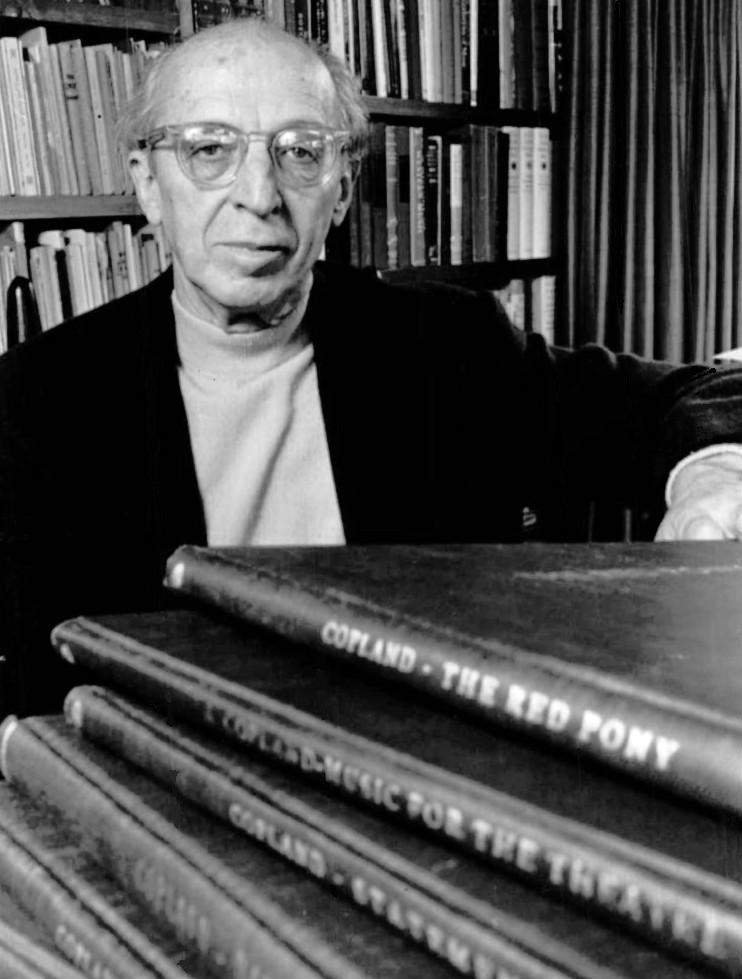

Aaron Copland (, ; November 14, 1900December 2, 1990) was an American composer, composition teacher, writer, and later a conductor of his own and other American music. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as "the Dean of American Composers". The open, slowly changing harmonies in much of his music are typical of what many people consider to be the sound of American music, evoking the vast American landscape and pioneer spirit. He is best known for the works he wrote in the 1930s and 1940s in a deliberately accessible style often referred to as "populist" and which the composer labeled his "vernacular" style. Works in this vein include the ballets ''

Aaron Copland (, ; November 14, 1900December 2, 1990) was an American composer, composition teacher, writer, and later a conductor of his own and other American music. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as "the Dean of American Composers". The open, slowly changing harmonies in much of his music are typical of what many people consider to be the sound of American music, evoking the vast American landscape and pioneer spirit. He is best known for the works he wrote in the 1930s and 1940s in a deliberately accessible style often referred to as "populist" and which the composer labeled his "vernacular" style. Works in this vein include the ballets ''

Aaron Copland was born in

Aaron Copland was born in

Copland's passion for the latest European music, plus glowing letters from his friend Aaron Schaffer, inspired him to go to Paris for further study. An article in ''

Copland's passion for the latest European music, plus glowing letters from his friend Aaron Schaffer, inspired him to go to Paris for further study. An article in ''

After a fruitful stay in Paris, Copland returned to America optimistic and enthusiastic about the future, determined to make his way as a full-time composer. He rented a studio apartment on New York City's

After a fruitful stay in Paris, Copland returned to America optimistic and enthusiastic about the future, determined to make his way as a full-time composer. He rented a studio apartment on New York City's  Inspired by the example of

Inspired by the example of

Appalachian Spring

''Appalachian Spring'' is a musical composition by Aaron Copland that was premiered in 1944 and has achieved widespread and enduring popularity as an orchestral suite. The music, scored for a thirteen-member chamber orchestra, was created upon c ...

'', ''Billy the Kid

Billy the Kid (born Henry McCarty; September 17 or November 23, 1859July 14, 1881), also known by the pseudonym William H. Bonney, was an outlaw and gunfighter of the American Old West, who killed eight men before he was shot and killed at t ...

'' and ''Rodeo

Rodeo () is a competitive equestrian sport that arose out of the working practices of cattle herding in Spain and Mexico, expanding throughout the Americas and to other nations. It was originally based on the skills required of the working va ...

'', his ''Fanfare for the Common Man

''Fanfare for the Common Man'' is a musical work by the American composer Aaron Copland. It was written in 1942 for the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra under conductor Eugene Goossens and was inspired in part by a speech made earlier that year ...

'' and Third Symphony. In addition to his ballets and orchestral works, he produced music in many other genres, including chamber music, vocal works, opera and film scores.

After some initial studies with composer Rubin Goldmark

Rubin Goldmark (August 15, 1872 – March 6, 1936) was an American composer, pianist, and educator.Perlis, ''New Grove Dictionary of American Music'', v. II, p. 239 Although in his time he was an often-performed American nationalist composer, hi ...

, Copland traveled to Paris, where he first studied with Isidor Philipp

Isidor Edmond Philipp (first name sometimes spelled Isidore) (2 September 1863 – 20 February 1958) was a French pianist, composer, and pedagogue of Jewish Hungarian descent. He was born in Budapest and died in Paris.

Biography

Isidor Philipp ...

and Paul Vidal

Paul Antonin Vidal (16 June 1863 – 9 April 1931) was a French composer, conductor and music teacher mainly active in Paris.Charlton D. Paul Vidal. In: ''The New Grove Dictionary of Opera.'' Macmillan, London and New York, 1997.

Life and caree ...

, then with noted pedagogue

Pedagogy (), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken a ...

Nadia Boulanger

Juliette Nadia Boulanger (; 16 September 188722 October 1979) was a French music teacher and conductor. She taught many of the leading composers and musicians of the 20th century, and also performed occasionally as a pianist and organist.

From a ...

. He studied three years with Boulanger, whose eclectic approach to music inspired his own broad taste. Determined upon his return to the U.S. to make his way as a full-time composer, Copland gave lecture-recitals, wrote works on commission and did some teaching and writing. However, he found that composing orchestral music in the modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

style, which he had adopted while studying abroad, was a financially contradictory approach, particularly in light of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. He shifted in the mid-1930s to a more accessible musical style which mirrored the German idea of ("music for use"), music that could serve utilitarian and artistic purposes. During the Depression years, he traveled extensively to Europe, Africa, and Mexico, formed an important friendship with Mexican composer Carlos Chávez

Carlos Antonio de Padua Chávez y Ramírez (13 June 1899 – 2 August 1978) was a Mexican composer, conductor, music theorist, educator, journalist, and founder and director of the Mexican Symphonic Orchestra. He was influenced by nativ ...

and began composing his signature works.

During the late 1940s, Copland became aware that Stravinsky and other fellow composers had begun to study Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

's use of twelve-tone (serial) techniques. After he had been exposed to the works of French composer Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mont ...

, he incorporated serial techniques into his ''Piano Quartet'' (1950), ''Piano Fantasy'' (1957), ''Connotations

A connotation is a commonly understood cultural or emotional association that any given word or phrase carries, in addition to its explicit or literal meaning, which is its denotation.

A connotation is frequently described as either positive or ...

'' for orchestra (1961) and ''Inscape

Inscape and instress are complementary and enigmatic concepts about individuality and uniqueness derived by the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins from the ideas of the medieval philosopher Duns Scotus.Chevigny, Bell Gale. Instress and Devotion in the ...

'' for orchestra (1967). Unlike Schoenberg, Copland used his tone rows in much the same fashion as his tonal material—as sources for melodies and harmonies, rather than as complete statements in their own right, except for crucial events from a structural point of view. From the 1960s onward, Copland's activities turned more from composing to conducting. He became a frequent guest conductor of orchestras in the U.S. and the UK and made a series of recordings of his music, primarily for Columbia Records

Columbia Records is an American record label owned by Sony Music, Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation of America, the North American division of Japanese Conglomerate (company), conglomerate Sony. It was founded on Janua ...

.

Life

Early years

Aaron Copland was born in

Aaron Copland was born in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, New York, on November 14, 1900. He was the youngest of five children in a Conservative Jewish

Conservative Judaism, known as Masorti Judaism outside North America, is a Jewish religious movement which regards the authority of ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and traditions as coming primarily from its people and community through the generat ...

family of Lithuanian origins. While emigrating from Russia to the United States, Copland's father, Harris Morris Copland (1864–1945), lived and worked in Scotland for two to three years to pay for his boat fare to the United States. It was there that Copland's father may have Anglicized

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influenc ...

his surname "Kaplan" to "Copland," though Copland himself believed for many years that the change had been due to an Ellis Island

Ellis Island is a federally owned island in New York Harbor, situated within the U.S. states of New York and New Jersey, that was the busiest immigrant inspection and processing station in the United States. From 1892 to 1954, nearly 12 mi ...

immigration official when his father entered the country. Copland was, however, unaware until late in his life that the family name had been Kaplan, and his parents never told him this. Throughout his childhood, Copland and his family lived above his parents' Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

shop, H. M. Copland's, at 628 Washington Avenue (which Aaron would later describe as "a kind of neighborhood Macy's

Macy's (originally R. H. Macy & Co.) is an American chain of high-end department stores founded in 1858 by Rowland Hussey Macy. It became a division of the Cincinnati-based Federated Department Stores in 1994, through which it is affiliated wi ...

"), on the corner of Dean Street and Washington Avenue, and most of the children helped out in the store. His father was a staunch Democrat. The family members were active in Congregation Baith Israel Anshei Emes

Congregation Baith Israel Anshei Emes ( he, בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל אַנְשֵׁי אֱמֶת, "House of Israel – People of Truth"), more commonly known as the Kane Street Synagogue, is an Women in Judaism#Conservative Judaism, egal ...

, where Aaron celebrated his bar mitzvah. Not especially athletic, the sensitive young man became an avid reader and often read Horatio Alger stories on his front steps.

Copland's father had no musical interest. His mother, Sarah Mittenthal Copland (1865–1942), sang, played the piano, and arranged for music lessons for her children. Copland had four older siblings: two older brothers, Ralph Copland (1888–1952) and Leon Copland (c. 1891–?) and two older sisters, Laurine Copland (c. 1892–?) and Josephine Copland (c. 1894–?). Of his siblings, his oldest brother Ralph was the most advanced musically; he was proficient on the violin. His sister Laurine had the strongest connection with Aaron; she gave him his first piano lessons, promoted his musical education, and supported him in his musical career. A student at the Metropolitan Opera School and a frequent opera-goer, Laurine also brought home libretti

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the text of major l ...

for Aaron to study. Copland attended Boys High School

Single-sex education, also known as single-gender education and gender-isolated education, is the practice of conducting education with male and female students attending separate classes, perhaps in separate buildings or schools. The practice of ...

and in the summer went to various camps. Most of his early exposure to music was at Jewish weddings and ceremonies, and occasional family musicales.

Copland began writing songs at the age of eight and a half. His earliest notated music, about seven bars he wrote when age 11, was for an opera scenario he created and called ''Zenatello''. From 1913 to 1917 he took piano lessons with Leopold Wolfsohn, who taught him the standard classical fare. Copland's first public music performance was at a Wanamaker's

John Wanamaker Department Store was one of the first department stores in the United States. Founded by John Wanamaker in Philadelphia, it was influential in the development of the retail industry including as the first store to use price tags. ...

recital. By the age of 15, after attending a concert by Polish composer-pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (; – 29 June 1941) was a Polish pianist and composer who became a spokesman for Polish independence. In 1919, he was the new nation's Prime Minister and foreign minister during which he signed the Treaty of Versaill ...

, Copland decided to become a composer. At age 16, Copland heard his first symphony at the Brooklyn Academy of Music

The Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) is a performing arts venue in Brooklyn, New York City, known as a center for progressive and avant-garde performance. It presented its first performance in 1861 and began operations in its present location in ...

. After attempts to further his music study from a correspondence course

Distance education, also known as distance learning, is the education of students who may not always be physically present at a school, or where the learner and the teacher are separated in both time and distance. Traditionally, this usually in ...

, Copland took formal lessons in harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. However ...

, theory

A theory is a rational type of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the results of such thinking. The process of contemplative and rational thinking is often associated with such processes as observational study or research. Theories may be ...

, and composition

Composition or Compositions may refer to:

Arts and literature

*Composition (dance), practice and teaching of choreography

*Composition (language), in literature and rhetoric, producing a work in spoken tradition and written discourse, to include v ...

from Rubin Goldmark

Rubin Goldmark (August 15, 1872 – March 6, 1936) was an American composer, pianist, and educator.Perlis, ''New Grove Dictionary of American Music'', v. II, p. 239 Although in his time he was an often-performed American nationalist composer, hi ...

, a noted teacher and composer of American music (who had given George Gershwin

George Gershwin (; born Jacob Gershwine; September 26, 1898 – July 11, 1937) was an American composer and pianist whose compositions spanned popular, jazz and classical genres. Among his best-known works are the orchestral compositions ' ...

three lessons). Goldmark, with whom Copland studied between 1917 and 1921, gave the young Copland a solid foundation, especially in the Germanic tradition. As Copland stated later: "This was a stroke of luck for me. I was spared the floundering that so many musicians have suffered through incompetent teaching." But Copland also commented that the maestro had "little sympathy for the advanced musical idioms of the day" and his "approved" composers ended with Richard Strauss.

Copland's graduation piece from his studies with Goldmark was a three-movement piano sonata in a Romantic style

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

. But he had also composed more original and daring pieces which he did not share with his teacher. In addition to regularly attending the Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera (commonly known as the Met) is an American opera company based in New York City, resident at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, currently situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The company is operat ...

and the New York Symphony

The New York Symphony Orchestra was founded as the New York Symphony Society in New York City by Leopold Damrosch in 1878. For many years it was a rival to the older Philharmonic Symphony Society of New York. It was supported by Andrew Carnegie, ...

, where he heard the standard classical repertory, Copland continued his musical development through an expanding circle of musical friends. After graduating from high school, Copland played in dance bands. Continuing his musical education, he received further piano lessons from Victor Wittgenstein, who found his student to be "quiet, shy, well-mannered, and gracious in accepting criticism." Copland's fascination with the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

and its promise for freeing the lower classes drew a rebuke from his father and uncles. In spite of that, in his early adult life, Copland would develop friendships with people with socialist and communist leanings.

Study in Paris

Copland's passion for the latest European music, plus glowing letters from his friend Aaron Schaffer, inspired him to go to Paris for further study. An article in ''

Copland's passion for the latest European music, plus glowing letters from his friend Aaron Schaffer, inspired him to go to Paris for further study. An article in ''Musical America

''Musical America'' is the oldest American magazine on classical music, first appearing in 1898 in print and in 1999 online, at musicalamerica.com. It is published by Performing Arts Resources, LLC, of East Windsor, New Jersey.

History 1898–19 ...

'' about a summer school program for American musicians at the Fontainebleau School of Music

The Fontainebleau Schools were founded in 1921, and consist of two schools: ''The American Conservatory'', and the ''School of Fine Arts at Fontainebleau''.

History

When the United States entered First World War the commander of its army, Genera ...

, offered by the French government, encouraged Copland still further. His father wanted him to go to college, but his mother's vote in the family conference allowed him to give Paris a try. On arriving in France, he studied at Fontainebleau with pianist and pedagogue Isidor Philipp

Isidor Edmond Philipp (first name sometimes spelled Isidore) (2 September 1863 – 20 February 1958) was a French pianist, composer, and pedagogue of Jewish Hungarian descent. He was born in Budapest and died in Paris.

Biography

Isidor Philipp ...

and composer Paul Vidal

Paul Antonin Vidal (16 June 1863 – 9 April 1931) was a French composer, conductor and music teacher mainly active in Paris.Charlton D. Paul Vidal. In: ''The New Grove Dictionary of Opera.'' Macmillan, London and New York, 1997.

Life and caree ...

. When Copland found Vidal too much like Goldmark, he switched at the suggestion of a fellow student to Nadia Boulanger

Juliette Nadia Boulanger (; 16 September 188722 October 1979) was a French music teacher and conductor. She taught many of the leading composers and musicians of the 20th century, and also performed occasionally as a pianist and organist.

From a ...

, then aged 34. He had initial reservations: "No one to my knowledge had ever before thought of studying with a woman." She interviewed him, and recalled later: "One could tell his talent immediately."

Boulanger had as many as 40 students at once and employed a formal regimen that Copland had to follow. Copland found her incisive mind much to his liking and found her ability to critique a composition impeccable. Boulanger "could always find the weak spot in a place you suspected was weak... She also could tell you ''why'' it was weak talics Copland" He wrote in a letter to his brother Ralph, "This intellectual Amazon is not only professor at the Conservatoire

A music school is an educational institution specialized in the study, training, and research of music. Such an institution can also be known as a school of music, music academy, music faculty, college of music, music department (of a larger ins ...

, is not only familiar with all music from Bach to Stravinsky, but is prepared for anything worse in the way of dissonance. But make no mistake ... A more charming womanly woman never lived." Copland later wrote that "it was wonderful for me to find a teacher with such openness of mind, while at the same time she held firm ideas of right and wrong in musical matters. The confidence she had in my talents and her belief in me were at the very least flattering and more -- they were crucial to my development at this time of my career." Though he had planned on only one year abroad, he studied with her for three years, finding that her eclectic approach inspired his own broad musical taste.

Along with his studies with Boulanger, Copland took classes in French language and history at the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

, attended plays, and frequented Shakespeare and Company, the English-language bookstore that was a gathering-place for expatriate American writers. Among this group in the heady cultural atmosphere of Paris in the 1920s were Paul Bowles

Paul Frederic Bowles (; December 30, 1910November 18, 1999) was an American expatriate composer, author, and translator. He became associated with the Moroccan city of Tangier, where he settled in 1947 and lived for 52 years to the end of his ...

, Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fic ...

, Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was ...

, Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the Allegheny West neighborhood and raised in Oakland, California, Stein moved to Paris ...

, and Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Fascism, fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II. His works ...

, as well as artists like Pablo Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and Scenic design, theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th ce ...

, Marc Chagall, and Amedeo Modigliani

Amedeo Clemente Modigliani (, ; 12 July 1884 – 24 January 1920) was an Italian painter and sculptor who worked mainly in France. He is known for portraits and nudes in a modern style characterized by a surreal elongation of faces, necks, and ...

. Also influential on the new music were the French intellectuals Marcel Proust, Paul Valéry

Ambroise Paul Toussaint Jules Valéry (; 30 October 1871 – 20 July 1945) was a French poet, essayist, and philosopher. In addition to his poetry and fiction (drama and dialogues), his interests included aphorisms on art, history, letters, mus ...

, Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism (and phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and lit ...

, and André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1947). Gide's career ranged from its beginnings in the Symbolism (arts), symbolist movement, to the advent o ...

; the latter cited by Copland as being his personal favorite and most read. Travels to Italy, Austria, and Germany rounded out Copland's musical education. During his stay in Paris, Copland began writing musical critiques, the first on Gabriel Fauré

Gabriel Urbain Fauré (; 12 May 1845 – 4 November 1924) was a French composer, organist, pianist and teacher. He was one of the foremost French composers of his generation, and his musical style influenced many 20th-century composers ...

, which helped spread his fame and stature in the music community.

1925 to 1935

After a fruitful stay in Paris, Copland returned to America optimistic and enthusiastic about the future, determined to make his way as a full-time composer. He rented a studio apartment on New York City's

After a fruitful stay in Paris, Copland returned to America optimistic and enthusiastic about the future, determined to make his way as a full-time composer. He rented a studio apartment on New York City's Upper West Side

The Upper West Side (UWS) is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Central Park on the east, the Hudson River on the west, West 59th Street to the south, and West 110th Street to the north. The Upper West ...

in the Empire Hotel, close to Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

and other musical venues and publishers. He remained in that area for the next 30 years, later moving to Westchester County, New York

Westchester County is located in the U.S. state of New York. It is the seventh most populous county in the State of New York and the most populous north of New York City. According to the 2020 United States Census, the county had a population o ...

. Copland lived frugally and survived financially with help from two $2,500 Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowships are grants that have been awarded annually since by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those "who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the ar ...

s in 1925 and 1926 (each of the two ). Lecture-recitals, awards, appointments, and small commissions, plus some teaching, writing, and personal loans, kept him afloat in the subsequent years through World War II. Also important, especially during the Depression, were wealthy patrons who underwrote performances, helped pay for publication of works and promoted musical events and composers. Among those mentors was Serge Koussevitzky, the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and known as a champion of "new music." Koussevitsky would prove to be very influential in Copland's life, and was perhaps the second most important figure in Copland's career after Boulanger. Beginning with the Symphony for Organ and Orchestra (1924), Koussevitzky would perform more of Copland's music than that of any the composer's contemporaries, at a time when other conductors were programming only a few of Copland's works.

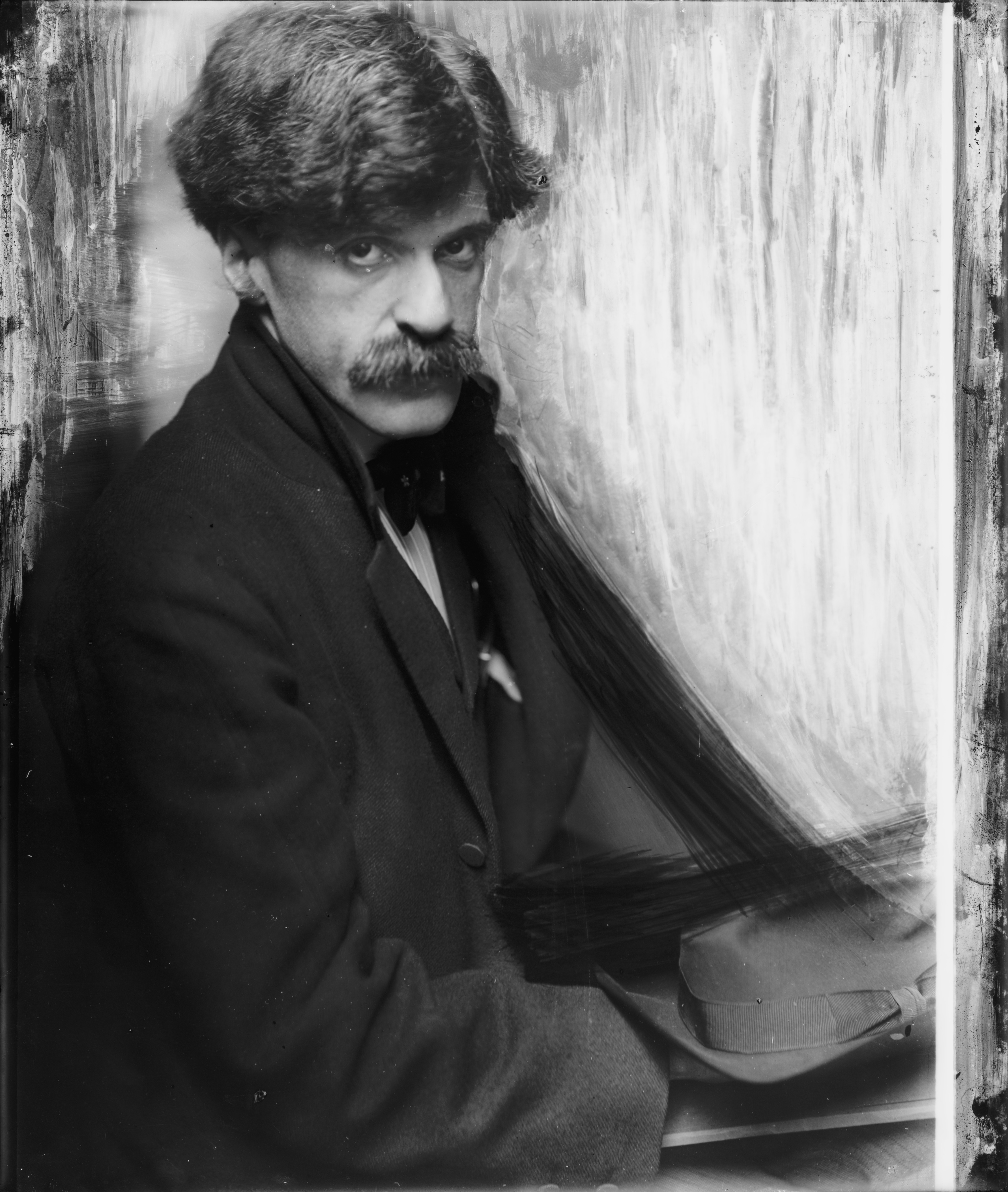

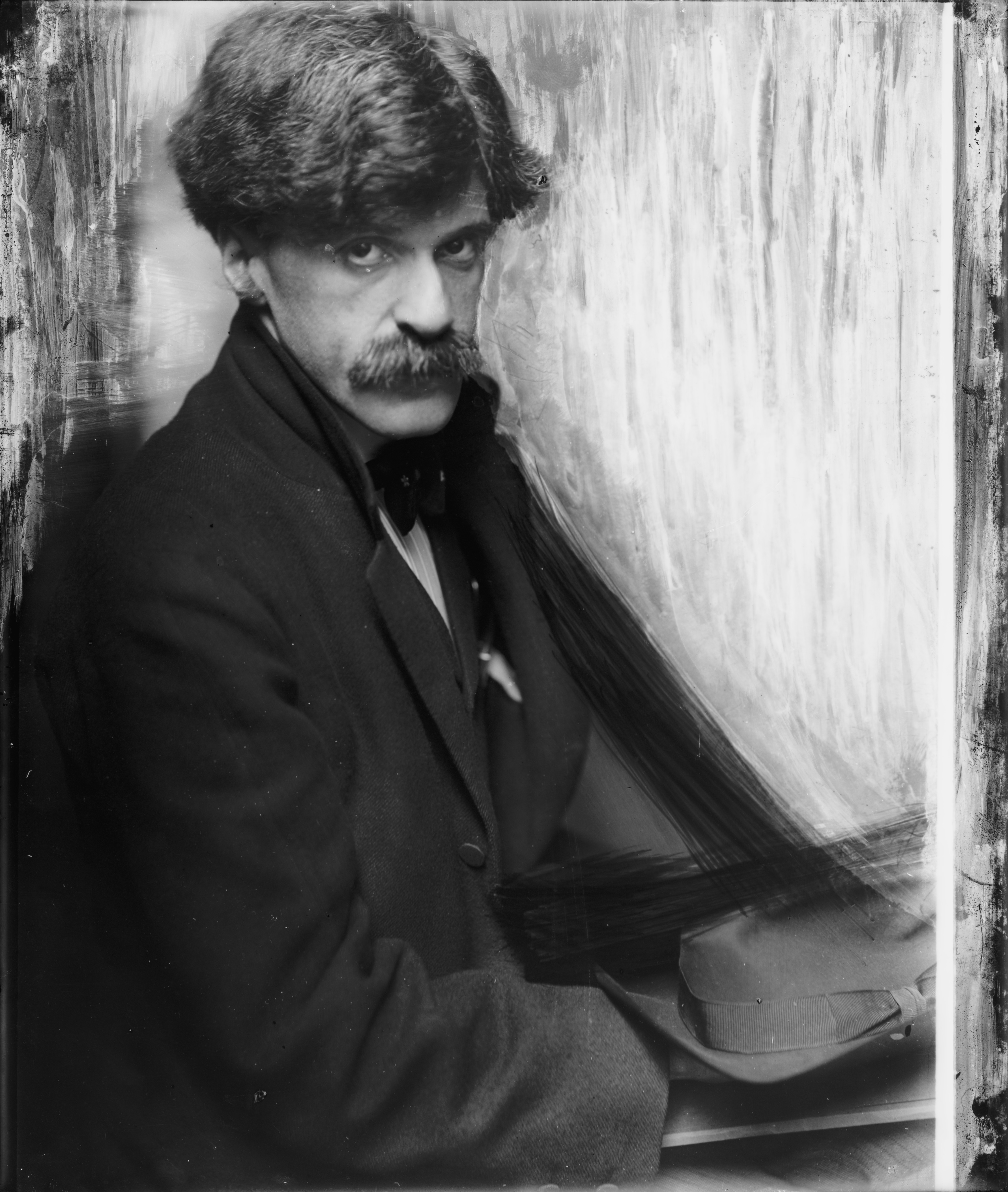

Soon after his return to the United States, Copland was exposed to the artistic circle of photographer Alfred Stieglitz. While Copland did not care for Stieglitz's domineering attitude, he did admire his work and took to heart Stieglitz's conviction that American artists should reflect "the ideas of American Democracy." This ideal influenced not just the composer, but also a generation of artists and photographers, including Paul Strand

Paul Strand (October 16, 1890 – March 31, 1976) was an American photographer and filmmaker who, along with fellow modernist photographers like Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston, helped establish photography as an art form in the 20th century. ...

, Edward Weston

Edward Henry Weston (March 24, 1886 – January 1, 1958) was a 20th-century American photographer. He has been called "one of the most innovative and influential American photographers..." and "one of the masters of 20th century photography." ...

, Ansel Adams

Ansel Easton Adams (February 20, 1902 – April 22, 1984) was an American landscape photographer and environmentalist known for his black-and-white images of the American West. He helped found Group f/64, an association of photographers advoca ...

, Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia Totto O'Keeffe (November 15, 1887 – March 6, 1986) was an American modernist artist. She was known for her paintings of enlarged flowers, New York skyscrapers, and New Mexico landscapes. O'Keeffe has been called the "Mother of Ame ...

, and Walker Evans

Walker Evans (November 3, 1903 – April 10, 1975) was an American photographer and photojournalist best known for his work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) documenting the effects of the Great Depression. Much of Evans' work from ...

. Evans's photographs inspired portions of Copland's opera ''The Tender Land

''The Tender Land'' is an opera with music by Aaron Copland and libretto by Horace Everett, a pseudonym for Erik Johns.

History

The opera tells of a farm family in the Midwest of the United States. Copland was inspired to write this opera aft ...

''.

In his quest to take up the slogan of the Stieglitz group, "Affirm America," Copland found only the music of Carl Ruggles

Carl Ruggles (born Charles Sprague Ruggles; March 11, 1876 – October 24, 1971) was an American composer, painter and teacher. His pieces employed "dissonant counterpoint", a term coined by fellow composer and musicologist Charles Seeger ...

and Charles Ives upon which to draw. Without what Copland called a "usable past" in American classical composers, he looked toward jazz and popular music, something he had already started to do while in Europe. In the 1920s, Gershwin, Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith (April 15, 1894 – September 26, 1937) was an American blues singer widely renowned during the Jazz Age. Nicknamed the " Empress of the Blues", she was the most popular female blues singer of the 1930s. Inducted into the Rock a ...

, and Louis Armstrong

Louis Daniel Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971), nicknamed "Satchmo", "Satch", and "Pops", was an American trumpeter and vocalist. He was among the most influential figures in jazz. His career spanned five decades and several era ...

were in the forefront of American popular music and jazz. By the end of the decade, Copland felt his music was going in a more abstract, less jazz-oriented direction. However, as large swing bands such as those of Benny Goodman

Benjamin David Goodman (May 30, 1909 – June 13, 1986) was an American clarinetist and bandleader known as the "King of Swing".

From 1936 until the mid-1940s, Goodman led one of the most popular swing big bands in the United States. His co ...

and Glenn Miller became popular in the 1930s, Copland took a renewed interest in the genre.

Inspired by the example of

Inspired by the example of Les Six

"Les Six" () is a name given to a group of six composers, five of them French and one Swiss, who lived and worked in Montparnasse. The name, inspired by Mily Balakirev's '' The Five'', originates in two 1920 articles by critic Henri Collet in '' ...

in France, Copland sought out contemporaries such as Roger Sessions

Roger Huntington Sessions (December 28, 1896March 16, 1985) was an American composer, teacher and musicologist. He had initially started his career writing in a neoclassical style, but gradually moved further towards more complex harmonies and ...

, Roy Harris

Roy Ellsworth Harris (February 12, 1898 – October 1, 1979) was an American composer. He wrote music on American subjects, and is best known for his Symphony No. 3.

Life

Harris was born in Chandler, Oklahoma on February 12, 1898. His ancestr ...

, Virgil Thomson

Virgil Thomson (November 25, 1896 – September 30, 1989) was an American composer and critic. He was instrumental in the development of the "American Sound" in classical music. He has been described as a modernist, a neoromantic, a neoclass ...

, and Walter Piston

Walter Hamor Piston, Jr. (January 20, 1894 – November 12, 1976), was an American composer of classical music, music theorist, and professor of music at Harvard University.

Life

Piston was born in Rockland, Maine at 15 Ocean Street to Walter Ha ...

, and quickly established himself as a spokesperson for composers of his generation. He also helped found the Copland-Sessions Concerts to showcase these composers' chamber works to new audiences. Copland's relationship with these men, who became known as "commando unit," was one of both support and rivalry, and he played a key role in keeping them together until after World War II. He also was generous with his time, with nearly every American young composer he met during his life, later earning the title "Dean of American Music."

With the knowledge he had gained from his studies in Paris, Copland came into demand as a lecturer and writer on contemporary European classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" also ...

. From 1927 to 1930 and from 1935 to 1938, he taught classes at The New School for Social Research

The New School for Social Research (NSSR) is a graduate-level educational institution that is one of the divisions of The New School in New York City, United States. The university was founded in 1919 as a home for progressive era thinkers. NSS ...

in New York City. Eventually, his New School lectures would appear in the form of two books —''What to Listen for in Music'' (1937, revised 1957) and ''Our New Music'' (1940, revised 1968 and retitled ''The New Music: 1900–1960''). During this period, Copland also wrote regularly for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', ''The Musical Quarterly

''The Musical Quarterly'' is the oldest academic journal on music in America. Originally established in 1915 by Oscar Sonneck, the journal was edited by Sonneck until his death in 1928. Sonneck was succeeded by a number of editors, including Ca ...

'' and a number of other journals. These articles would appear in 1969 as the book ''Copland on Music''. During his time at The New School, Copland was active as a presenter and curator, using The New School as a key location to present a wide range of composers and artists from the United States as well as across the globe.

Copland's compositions in the early 1920s reflected the modernist attitude that prevailed among intellectuals, that the arts need be accessible to only a cadre of the enlightened, and that the masses would come to appreciate their efforts over time. However, mounting troubles with the ''Symphonic Ode'' (1929) and '' Short Symphony'' (1933) caused Copland to rethink this approach. It was financially contradictory, particularly during the Depression. Avant-garde music had lost what cultural historian Morris Dickstein

Morris Dickstein (February 23, 1940 – March 24, 2021) was an American literary scholar, cultural historian, professor, essayist, book critic, and public intellectual. He was Distinguished Professor Emeritus of English at CUNY Graduate Center in ...

calls "its buoyant experimental edge" and the national mood toward it had changed. As biographer Howard Pollack

Howard Pollack (born March 17, 1952) is a prominent American pianist and musicologist, known for his biographies of American composers.

Biography

Pollack was born in Brooklyn and studied piano with Jennie Glickman while attending James Madison H ...

points out,

Copland observed two trends among composers in the 1930s: first, a continuing attempt to "simplify their musical language" and, second, a desire to "make contact" with as wide an audience as possible. Since 1927, he had been in the process of simplifying, or at least paring down, his musical language, though in such a manner as to sometimes have the effect, paradoxically, of estranging audiences and performers. By 1933 ... he began to find ways to make his starkly personal language accessible to a surprisingly large number of people.In many ways, this shift mirrored the German idea of ("music for use"), as composers sought to create music that could serve a

utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

as well as artistic purpose. This approach encompassed two trends: first, music that students could easily learn, and second, music which would have wider appeal, such as incidental music for plays, movies, radio, etc. Toward this end, Copland provided musical advice and inspiration to The Group Theatre, a company which also attracted Stella Adler

Stella Adler (February 10, 1901 – December 21, 1992) was an American actress and acting teacher.

''

''

Elia Kazan and

Concurrent with ''The Second Hurricane'', Copland composed (for radio broadcast) "Prairie Journal" on a commission from the

Concurrent with ''The Second Hurricane'', Copland composed (for radio broadcast) "Prairie Journal" on a commission from the  The 1940s were arguably Copland's most productive years, and some of his works from this period would cement his worldwide fame. His ballet scores for ''

The 1940s were arguably Copland's most productive years, and some of his works from this period would cement his worldwide fame. His ballet scores for ''

In 1950, Copland received a U.S.-Italy Fulbright Commission scholarship to study in Rome, which he did the following year. Around this time, he also composed his Piano Quartet, adopting Schoenberg's twelve-tone method of composition, and ''

In 1950, Copland received a U.S.-Italy Fulbright Commission scholarship to study in Rome, which he did the following year. Around this time, he also composed his Piano Quartet, adopting Schoenberg's twelve-tone method of composition, and ''

From 1960 until his death, Copland resided at

From 1960 until his death, Copland resided at

Pollack states that Copland was gay and that the composer came to an early acceptance and understanding of his sexuality. Like many at that time, Copland guarded his privacy, especially in regard to his homosexuality. He provided few written details about his private life, and even after the Stonewall riots of 1969, showed no inclination to "come out." However, he was one of the few composers of his stature to live openly and travel with his intimates. They tended to be talented, younger men involved in the arts, and the age-gap between them and the composer widened as he grew older. Most became enduring friends after a few years and, in Pollack's words, "remained a primary source of companionship." Among Copland's love affairs were ones with photographer

Pollack states that Copland was gay and that the composer came to an early acceptance and understanding of his sexuality. Like many at that time, Copland guarded his privacy, especially in regard to his homosexuality. He provided few written details about his private life, and even after the Stonewall riots of 1969, showed no inclination to "come out." However, he was one of the few composers of his stature to live openly and travel with his intimates. They tended to be talented, younger men involved in the arts, and the age-gap between them and the composer widened as he grew older. Most became enduring friends after a few years and, in Pollack's words, "remained a primary source of companionship." Among Copland's love affairs were ones with photographer

The Aaron Copland Collection

and th

Aaron Copland Collection

at the

A Tribute to Aaron Copland at American Music Preservation.com

Aaron Copland Oral History collection at Oral History of American Music

''Hoedown – Annie Moses Band''

Art of the States: Aaron CoplandAudio (.ram files) of a 1961 interview for the BBC (archive from March 15, 2012; accessed June 30, 2016)

Audio (.smil files) of a 1980 interview for NPR

Fanfare for America (video)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Copland, Aaron 1900 births 1990 deaths 20th-century American composers 20th-century American conductors (music) 20th-century American Jews 20th-century American male musicians 20th-century American male writers 20th-century classical composers 20th-century classical pianists 20th-century jazz composers 20th-century LGBT people American agnostics American classical composers American classical pianists American expatriates in France American film score composers American gay musicians American gay writers American jazz composers American jazz pianists American male classical composers American male classical pianists American male conductors (music) American male film score composers American male jazz composers American male jazz musicians American music educators American musical theatre composers American opera composers American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent American people of Russian-Jewish descent ASCAP composers and authors Ballet composers Best Original Music Score Academy Award winners Boys High School (Brooklyn) alumni Broadway composers and lyricists Classical musicians from New York (state) Columbia Records artists Composers for piano Composers from New York City Congressional Gold Medal recipients Danzón composers Deaths from Alzheimer's disease Deaths from respiratory failure Educators from New York City Grammy Award winners Hollywood blacklist Honorary Members of the Royal Philharmonic Society Jazz-influenced classical composers Jazz musicians from New York (state) Jewish agnostics Jewish American classical composers Jewish American classical musicians Jewish American film score composers Jewish American jazz composers Jewish American songwriters Jewish American writers Jewish classical pianists Jewish jazz musicians Kennedy Center honorees LGBT classical composers LGBT classical musicians LGBT film score composers LGBT jazz composers LGBT Jews LGBT people from New York (state) American LGBT writers MacDowell Colony fellows Male musical theatre composers Male opera composers Modernist composers Music & Arts artists Musicians from Brooklyn Deaths from dementia in New York (state) Respiratory disease deaths in New York (state) People from Cortlandt Manor, New York People from the Upper West Side Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Presidents of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Pulitzer Prize for Music winners Pupils of Isidor Philipp Pupils of Paul Vidal Pupils of Rubin Goldmark Twelve-tone and serial composers United States National Medal of Arts recipients Writers from Brooklyn Fulbright alumni

Lee Strasberg

Lee Strasberg (born Israel Strassberg; November 17, 1901 – February 17, 1982) was an American theatre director, actor and acting teacher. He co-founded, with theatre directors Harold Clurman and Cheryl Crawford, the Group Theatre in 1931 ...

. Philosophically an outgrowth of Stieglitz and his ideals, the Group focused on socially relevant plays by the American authors. Through it and later his work in film, Copland met several major American playwrights, including Thornton Wilder

Thornton Niven Wilder (April 17, 1897 – December 7, 1975) was an American playwright and novelist. He won three Pulitzer Prizes — for the novel ''The Bridge of San Luis Rey'' and for the plays ''Our Town'' and ''The Skin of Our Teeth'' — a ...

, William Inge

William Motter Inge (; May 3, 1913 – June 10, 1973) was an American playwright and novelist, whose works typically feature solitary protagonists encumbered with strained sexual relations. In the early 1950s he had a string of memorable Broad ...

, Arthur Miller

Arthur Asher Miller (October 17, 1915 – February 10, 2005) was an American playwright, essayist and screenwriter in the 20th-century American theater. Among his most popular plays are '' All My Sons'' (1947), ''Death of a Salesman'' ( ...

, and Edward Albee, and considered projects with all of them.

1935 to 1950

Around 1935 Copland began to compose musical pieces for young audiences, in accordance with the first goal of American Gebrauchsmusik. These works included piano pieces (''The Young Pioneers'') and an opera (''The Second Hurricane

''The Second Hurricane'' is an opera in two acts by Aaron Copland to a libretto by Edwin Denby (poet), Edwin Denby. Specifically written for school performances, it lasts just under an hour and premiered on April 21, 1937, at the Henry Street Sett ...

''). During the Depression years, Copland traveled extensively to Europe, Africa, and Mexico. He formed an important friendship with Mexican composer Carlos Chávez

Carlos Antonio de Padua Chávez y Ramírez (13 June 1899 – 2 August 1978) was a Mexican composer, conductor, music theorist, educator, journalist, and founder and director of the Mexican Symphonic Orchestra. He was influenced by nativ ...

and would return often to Mexico for working vacations conducting engagements. During his initial visit to Mexico, Copland began composing the first of his signature works, ''El Salón México

''El Salón México'' is a symphonic composition in one movement by Aaron Copland, which uses Mexican folk music extensively. Copland began the work in 1932 and completed it in 1936, following several visits to Mexico. The four melodies of the ...

'', which he completed in 1936. In it and in ''The Second Hurricane'' Copland began "experimenting," as he phrased it, with a simpler, more accessible style. This and other incidental commissions fulfilled the second goal of American Gebrauchsmusik, creating music of wide appeal.

Concurrent with ''The Second Hurricane'', Copland composed (for radio broadcast) "Prairie Journal" on a commission from the

Concurrent with ''The Second Hurricane'', Copland composed (for radio broadcast) "Prairie Journal" on a commission from the Columbia Broadcast System

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainm ...

. This was one of his first pieces to convey the landscape of the American West. This emphasis on the frontier carried over to his ballet ''Billy the Kid

Billy the Kid (born Henry McCarty; September 17 or November 23, 1859July 14, 1881), also known by the pseudonym William H. Bonney, was an outlaw and gunfighter of the American Old West, who killed eight men before he was shot and killed at t ...

'' (1938), which along with ''El Salón México'' became his first widespread public success. Copland's ballet music established him as an authentic composer of American music much as Stravinsky's ballet scores connected the composer with Russian music and came at an opportune time. He helped fill a vacuum for American choreographers to fill their dance repertory and tapped into an artistic groundswell, from the motion pictures of Busby Berkeley

Busby Berkeley (born Berkeley William Enos; November 29, 1895 – March 14, 1976) was an American film director and musical choreographer. Berkeley devised elaborate musical production numbers that often involved complex geometric patterns. Berke ...

and Fred Astaire

Fred Astaire (born Frederick Austerlitz; May 10, 1899 – June 22, 1987) was an American dancer, choreographer, actor, and singer. He is often called the greatest dancer in Hollywood film history.

Astaire's career in stage, film, and tele ...

to the ballets of George Balanchine and Martha Graham, to both democratize and Americanize dance as an art form. In 1938, Copland helped form the American Composers Alliance to promote and publish American contemporary classical music. Copland was president of the organization from 1939 to 1945. In 1939, Copland completed his first two Hollywood film scores, for ''Of Mice and Men

''Of Mice and Men'' is a novella written by John Steinbeck. Published in 1937, it narrates the experiences of George Milton and Lennie Small, two displaced migrant ranch workers, who move from place to place in California in search of new job o ...

'' and ''Our Town

''Our Town'' is a 1938 metatheatrical three-act play by American playwright Thornton Wilder which won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. The play tells the story of the fictional American small town of Grover's Corners between 1901 and 1913 thro ...

'', and composed the radio score "John Henry," based on the folk ballad.

While these works and others like them that would follow were accepted by the listening public at large, detractors accused Copland of pandering to the masses. Music critic Paul Rosenfeld, for one, warned in 1939 that Copland was "standing in the fork in the highroad, the two branches of which lead respectively to popular and artistic success." Even some of the composer's friends, such as composer Arthur Berger, were confused about Copland's simpler style. One, composer David Diamond, went so far as to lecture Copland: "By having sold out to the mongrel commercialists half-way already, the danger is going to be wider for you, and I beg you dear Aaron, don't sell out ntirelyyet." Copland's response was that his writing as he did and in as many genres was his response to how the Depression had affected society, as well as to new media and the audiences made available by these new media. As he himself phrased it, "The composer who is frightened of losing his artistic integrity through contact with a mass audience is no longer aware of the meaning of the word art."

The 1940s were arguably Copland's most productive years, and some of his works from this period would cement his worldwide fame. His ballet scores for ''

The 1940s were arguably Copland's most productive years, and some of his works from this period would cement his worldwide fame. His ballet scores for ''Rodeo

Rodeo () is a competitive equestrian sport that arose out of the working practices of cattle herding in Spain and Mexico, expanding throughout the Americas and to other nations. It was originally based on the skills required of the working va ...

'' (1942) and ''Appalachian Spring

''Appalachian Spring'' is a musical composition by Aaron Copland that was premiered in 1944 and has achieved widespread and enduring popularity as an orchestral suite. The music, scored for a thirteen-member chamber orchestra, was created upon c ...

'' (1944) were huge successes. His pieces ''Lincoln Portrait

''Lincoln Portrait'' (also known as ''A Lincoln Portrait'') is a classical orchestral work written by the American composer Aaron Copland. The work involves a full orchestra, with particular emphasis on the brass section at climactic moments. The ...

'' and ''Fanfare for the Common Man

''Fanfare for the Common Man'' is a musical work by the American composer Aaron Copland. It was written in 1942 for the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra under conductor Eugene Goossens and was inspired in part by a speech made earlier that year ...

'' became patriotic standards. Also important was the Third Symphony. Composed in a two-year period from 1944 to 1946, it became Copland's best-known symphony. The Clarinet Concerto

A clarinet concerto is a concerto for clarinet; that is, a musical composition for solo clarinet together with a large ensemble (such as an orchestra or concert band). Albert Rice has identified a work by Giuseppe Antonio Paganelli as possibly th ...

(1948), scored for solo clarinet, strings, harp, and piano, was a commission piece for bandleader and clarinetist Benny Goodman and a complement to Copland's earlier jazz-influenced work, the Piano Concerto (1926). His ''Four Piano Blues'' is an introspective composition with a jazz influence. Copland finished the 1940s with two film scores, one for William Wyler

William Wyler (; born Willi Wyler (); July 1, 1902 – July 27, 1981) was a Swiss-German-American film director and producer who won the Academy Award for Best Director three times, those being for '' Mrs. Miniver'' (1942), ''The Best Years of ...

's ''The Heiress

''The Heiress'' is a 1949 American romantic drama film directed and produced by William Wyler, from a screenplay written by Ruth and Augustus Goetz, adapted from their 1947 stage play of the same title, which was itself adapted from Henry Jame ...

'' and one for the film adaptation

A film adaptation is the transfer of a work or story, in whole or in part, to a feature film. Although often considered a type of derivative work, film adaptation has been conceptualized recently by academic scholars such as Robert Stam as a dial ...

of John Steinbeck

John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. (; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer and the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature winner "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social ...

's novel ''The Red Pony

''The Red Pony'' is an episodic novella written by American writer John Steinbeck in 1933. The first three chapters were published in magazines from 1933 to 1936. The full book was published in 1937 by Covici Friede. The stories in the book ar ...

''.

In 1949, Copland returned to Europe, where he found French composer Pierre Boulez dominating the group of post-war avant-garde composers there. He also met with proponents of twelve-tone technique, based on the works of Arnold Schoenberg, and found himself interested in adapting serial methods to his own musical voice.

1950s and 1960s

Old American Songs

''Old American Songs'' are two sets of songs arranged by Aaron Copland in 1950 and 1952 respectively, after research in the Sheet Music Collection of the Harris Collection of American Poetry and Plays, in the John Hay Library at Brown Universit ...

'' (1950), the first set of which was premiered by Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

, the second by William Warfield

William Caesar Warfield (January 22, 1920 – August 25, 2002) was an American concert bass-baritone singer and actor, known for his appearances in stage productions, Hollywood films, and television programs. A prominent African American artist ...

. During the 1951–52 academic year, Copland gave a series of lectures under the Charles Eliot Norton Professorship at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. These lectures were published as the book ''Music and Imagination''.

Because of his leftist

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

views, which had included his support of the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

ticket during the 1936 presidential election and his strong support of Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

candidate Henry A. Wallace during the 1948 presidential election, Copland was investigated by the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and its principal Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement age ...

during the Red scare

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which ar ...

of the 1950s. He was included on an FBI list of 151 artists thought to have Communist associations and found himself blacklisted, with ''A Lincoln Portrait'' withdrawn from the 1953 inaugural concert for President Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

. Called later that year to a private hearing at the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, Copland was questioned by Joseph McCarthy and Roy Cohn about his lecturing abroad and his affiliations with various organizations and events. In the process, McCarthy and Cohn neglected completely Copland's works, which made a virtue of American values. Outraged by the accusations, many members of the musical community held up Copland's music as a banner of his patriotism. The investigations ceased in 1955 and were closed in 1975.

The McCarthy probes did not seriously affect Copland's career and international artistic reputation, taxing of his time, energy, and emotional state as they might have been. Nevertheless, beginning in 1950, Copland—who had been appalled at Stalin's persecution of Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, , group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throughout his life as a major compo ...

and other artists—began resigning from participation in leftist groups. Copland, Pollack states, "stayed particularly concerned about the role of the artist in society". He decried the lack of artistic freedom in the Soviet Union, and in his 1954 Norton lecture he asserted that loss of freedom under Soviet Communism deprived artists of "the immemorial right of the artist to be wrong." He began to vote Democratic, first for Stevenson and then for Kennedy.

Potentially more damaging for Copland was a sea-change in artistic tastes, away from the Populist mores that infused his work of the 1930s and 40s. Beginning in the 1940s, intellectuals assailed Popular Front culture, to which Copland's music was linked, and labeled it, in Dickstein's words, as "hopelessly middlebrow, a dumbing down

Dumbing down is the deliberate oversimplification of intellectual content in education, literature, and cinema, news, video games, and culture. Originated in 1933, the term "dumbing down" was movie-business slang, used by screenplay writers, meani ...

of art into toothless entertainment." They often linked their disdain for Populist art with technology, new media and mass audiences—in other words, the areas of radio, television and motion pictures, for which Copland either had or soon would write music, as well as his popular ballets. While these attacks actually began at the end of the 1930s with the writings of Clement Greenberg

Clement Greenberg () (January 16, 1909 – May 7, 1994), occasionally writing under the pseudonym K. Hardesh, was an American essayist known mainly as an art critic closely associated with American modern art of the mid-20th century and a formali ...

and Dwight Macdonald

Dwight Macdonald (March 24, 1906 – December 19, 1982) was an American writer, editor, film critic, social critic, literary critic, philosopher, and activist. Macdonald was a member of the New York Intellectuals and editor of their leftist maga ...

for ''Partisan Review

''Partisan Review'' (''PR'') was a small-circulation quarterly "little magazine" dealing with literature, politics, and cultural commentary published in New York City. The magazine was launched in 1934 by the Communist Party USA–affiliated Joh ...

'', they were based in anti-Stalinist politics and would accelerate in the decades following World War II.

Despite any difficulties that his suspected Communist sympathies might have posed, Copland traveled extensively during the 1950s and early 1960s to observe the avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical ...

styles of Europe, hear compositions by Soviet composers not well known in the West, and experience the new school of Polish music. While in Japan, he was taken with the work of Tōru Takemitsu

was a Japanese composer and writer on aesthetics and music theory. Largely self-taught, Takemitsu was admired for the subtle manipulation of instrumental and orchestral timbre. He is known for combining elements of oriental and occidental phil ...

and began a correspondence with him that would last over the next decade. Copland revised his text "The New Music" with comments on the styles that he encountered. He found much of what he heard dull and impersonal. Electronic music

Electronic music is a genre of music that employs electronic musical instruments, digital instruments, or circuitry-based music technology in its creation. It includes both music made using electronic and electromechanical means ( electroac ...

seemed to have "a depressing sameness of sound," while aleatoric music

Aleatoric music (also aleatory music or chance music; from the Latin word ''alea'', meaning "dice") is music in which some element of the composition is left to chance, and/or some primary element of a composed work's realization is left to the ...

was for those "who enjoy teetering on the edge of chaos." As he summarized, "I've spent most of my life trying to get the right note in the right place. Just throwing it open to chance seems to go against my natural instincts."

In 1952, Copland received a commission from the League of Composers The League of Composers/ International Society for Contemporary Music is a society whose stated mission is "to produce the highest quality performances of new music, to champion American composers in the United States and abroad, and to introduce Am ...

, funded by a grant from Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, to write an opera for television. While Copland was aware of the potential pitfalls of that genre, which included weak libretti and demanding production values, he had also been thinking about writing an opera since the 1940s. Among the subjects he had considered were Theodore Dreiser

Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser (; August 27, 1871 – December 28, 1945) was an American novelist and journalist of the naturalist school. His novels often featured main characters who succeeded at their objectives despite a lack of a firm mora ...

's ''An American Tragedy

''An American Tragedy'' is a 1925 novel by American writer Theodore Dreiser. He began the manuscript in the summer of 1920, but a year later abandoned most of that text. It was based on the notorious murder of Grace Brown in 1906 and the trial of ...

'' and Frank Norris

Benjamin Franklin Norris Jr. (March 5, 1870 – October 25, 1902) was an American journalist and novelist during the Progressive Era, whose fiction was predominantly in the naturalist genre. His notable works include '' McTeague: A Story of San ...

's ''McTeague

''McTeague: A Story of San Francisco'', otherwise known as simply ''McTeague'', is a novel by Frank Norris, first published in 1899. It tells the story of a couple's courtship and marriage, and their subsequent descent into poverty and violence ...

'' He finally settled on James Agee's ''Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

''Let Us Now Praise Famous Men'' is a book with text by American writer James Agee and photographs by American photographer Walker Evans, first published in 1941 in the United States. The work documents the lives of impoverished tenant farmers ...

'', which seemed appropriate for the more intimate setting of television and could also be used in the "college trade," with more schools mounting operas than they had before World War II. The resulting opera, ''The Tender Land

''The Tender Land'' is an opera with music by Aaron Copland and libretto by Horace Everett, a pseudonym for Erik Johns.

History

The opera tells of a farm family in the Midwest of the United States. Copland was inspired to write this opera aft ...

'', was written in two acts but later expanded to three. As Copland feared, when the opera premiered in 1954 critics found the libretto to be weak. In spite of its flaws, the opera became one of the few American operas to enter the standard repertory.

In 1957, 1958, and 1976, Copland was the Music Director of the Ojai Music Festival

The Ojai Music Festival is an annual classical music festival in the United States. Held in Ojai, California (75 miles northwest of Los Angeles), for four days every June, the festival presents music, symposia, and educational programs emphasizi ...

, a classical and contemporary music festival in Ojai, California. For the occasion of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Centennial, Copland composed ''Ceremonial Fanfare for Brass Ensemble'' to accompany the exhibition "Masterpieces of Fifty Centuries." Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein ( ; August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was an American conductor, composer, pianist, music educator, author, and humanitarian. Considered to be one of the most important conductors of his time, he was the first America ...

, Piston, William Schuman

William Howard Schuman (August 4, 1910February 15, 1992) was an American composer and arts administrator.

Life

Schuman was born into a Jewish family in Manhattan, New York City, son of Samuel and Rachel Schuman. He was named after the 27th U.S. ...

, and Thomson also composed pieces for the Museum's Centennial exhibitions.

Later years

From the 1960s onward, Copland turned increasingly to conducting. Though not enamored with the prospect, he found himself without new ideas for composition, saying, "It was exactly as if someone had simply turned off a faucet." He became a frequent guest conductor in the United States and the United Kingdom and made a series of recordings of his music, primarily forColumbia Records

Columbia Records is an American record label owned by Sony Music, Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation of America, the North American division of Japanese Conglomerate (company), conglomerate Sony. It was founded on Janua ...

. In 1960, RCA Victor

RCA Records is an American record label currently owned by Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation of America. It is one of Sony Music's four flagship labels, alongside RCA's former long-time rival Columbia Records; also Aris ...

released Copland's recordings with the Boston Symphony Orchestra of the orchestral suites from ''Appalachian Spring'' and ''The Tender Land''; these recordings were later reissued on CD, as were most of Copland's Columbia recordings (by Sony).

From 1960 until his death, Copland resided at

From 1960 until his death, Copland resided at Cortlandt Manor, New York

Cortlandt Manor is a hamlet located in the Town of Cortlandt in northern Westchester County, New York, United States. Cortlandt Manor is situated directly east, north and south of Peekskill, and east of three sections of the Town of Cortlandt, ...

. Known as Rock Hill, his home was added to the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

in 2003 and further designated a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

in 2008. Copland's health deteriorated through the 1980s, and he died of Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegeneration, neurodegenerative disease that usually starts slowly and progressively worsens. It is the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in short-term me ...

and respiratory failure

Respiratory failure results from inadequate gas exchange by the respiratory system, meaning that the arterial oxygen, carbon dioxide, or both cannot be kept at normal levels. A drop in the oxygen carried in the blood is known as hypoxemia; a rise ...

on December 2, 1990, in North Tarrytown, New York

Sleepy Hollow is a village in the town of Mount Pleasant, in Westchester County, New York, United States. The village is located on the east bank of the Hudson River, about north of New York City, and is served by the Philipse Manor stop on ...

(now Sleepy Hollow). Following his death, his ashes were scattered over the Tanglewood Music Center near Lenox, Massachusetts. Much of his large estate was bequeathed to the creation of the Aaron Copland Fund for Composers, which bestows over $600,000 per year to performing groups.

Personal life

Copland never enrolled as a member of any political party. Nevertheless, he inherited a considerable interest in civic and world events from his father. His views were generally progressive and he had strong ties with numerous colleagues and friends in the Popular Front, including Odets. Early in his life, Copland developed, in Pollack's words, "a deep admiration for the works of Frank Norris, Theodore Dreiser andUpton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in seve ...

, all socialists whose novels passionately excoriated capitalism's physical and emotional toll on the average man." Even after the McCarthy hearings, he remained a committed opponent of militarism and the Cold War, which he regarded as having been instigated by the United States. He condemned it as "almost worse for art than the real thing." Throw the artist "into a mood of suspicion, ill-will, and dread that typifies the cold war attitude and he'll create nothing".

While Copland had various encounters with organized religious thought, which influenced some of his early compositions, he remained agnostic. He was close with Zionism during the Popular Front movement, when it was endorsed by the left. Pollack writes:

Like many contemporaries, Copland regarded Judaism alternately in terms of religion, culture, and race; but he showed relatively little involvement in any aspect of his Jewish heritage. At the same time, he had ties to Christianity, identifying with such profoundly Christian writers as Gerard Manley Hopkins and often spending Christmas Day at home with a special dinner with close friends. In general, his music seemed to evoke Protestant hymns as often as it did Jewish chant. Copland characteristically found connections among various religious traditions. But if Copland was discreet about his Jewish background, he never hid it, either.

Pollack states that Copland was gay and that the composer came to an early acceptance and understanding of his sexuality. Like many at that time, Copland guarded his privacy, especially in regard to his homosexuality. He provided few written details about his private life, and even after the Stonewall riots of 1969, showed no inclination to "come out." However, he was one of the few composers of his stature to live openly and travel with his intimates. They tended to be talented, younger men involved in the arts, and the age-gap between them and the composer widened as he grew older. Most became enduring friends after a few years and, in Pollack's words, "remained a primary source of companionship." Among Copland's love affairs were ones with photographer

Pollack states that Copland was gay and that the composer came to an early acceptance and understanding of his sexuality. Like many at that time, Copland guarded his privacy, especially in regard to his homosexuality. He provided few written details about his private life, and even after the Stonewall riots of 1969, showed no inclination to "come out." However, he was one of the few composers of his stature to live openly and travel with his intimates. They tended to be talented, younger men involved in the arts, and the age-gap between them and the composer widened as he grew older. Most became enduring friends after a few years and, in Pollack's words, "remained a primary source of companionship." Among Copland's love affairs were ones with photographer Victor Kraft

Victor Kraft (4 July 1880 – 3 January 1975) was an Austrian philosopher. He is best known for being a member of the Vienna Circle.

Early life and education

Kraft studied philosophy, geography and history at the University of Vienna. He partic ...

, artist Alvin Ross, pianist Paul Moor, dancer Erik Johns, composer John Brodbin Kennedy, and painter Prentiss Taylor.

Victor Kraft became a constant in Copland's life, though their romance might have ended by 1944. Originally a violin prodigy when the composer met him in 1932, Kraft gave up music to pursue a career in photography, in part due to Copland's urging. Kraft would leave and re-enter Copland's life, often bringing much stress with him as his behavior became increasingly erratic, sometimes confrontational. Kraft fathered a child to whom Copland later provided financial security, through a bequest from his estate.

Music